activity of the soul in accordance with virtue

Is Happiness a virtuous activity?

The answer to the question we are asking is plain also from the definition of happiness; for it has been said to be a virtuous activity of soul, of a certain kind. Of the remaining goods, some must necessarily pre-exist as conditions of happiness, and others are naturally co-operative and useful as instruments.

What does Aristotle say about a soul?

A soul, Aristotle says, is “the actuality of a body that has life,” where life means the capacity for self-sustenance, growth, and reproduction. If one regards a living substance as a composite of matter and form, then the soul is the form of a natural—or, as Aristotle sometimes says, organic—body.

What does Aristotle say about virtuous activity?

Aristotle’s statement implies that in order to determine whether (for example) the pleasure of virtuous activity is more desirable than that of eating, we are not to attend to the pleasures themselves but to the activities with which we are pleased. A pleasure’s goodness derives from the goodness of its associated activity.

Why is virtuous activity a good thing in life?

And as in the Olympic Games it is not the most beautiful and the strongest that are crowned but those who compete (for it is some of these that are victorious), so those who act win, and rightly win, the noble and good things in life. Virtue feels good. And, because happiness is virtuous activity… Their life is also in itself pleasant.

Overview

Aristotle regarded psychology as a part of natural philosophy, and he wrote much about the philosophy of mind. This material appears in his ethical writings, in a systematic treatise on the nature of the soul (De anima), and in a number of minor monographs on topics such as sense-perception, memory, sleep, and dreams. For Aristotle the biologist, the soul is not—as it was in some of Plato’s writings—an exile from a better world ill-housed in a base body. The soul’s very essence is defined by its relationship to an organic structure. Not only humans but beasts and plants too have souls, intrinsic principles of animal and vegetable life. A soul, Aristotle says, is “the actuality of a body that has life,” where life means the capacity for self-sustenance, growth, and reproduction. If one regards a living substance as a composite of matter and form, then the soul is the form of a natural—or, as Aristotle sometimes says, organic—body. An organic body is a body that has organs—that is to say, parts that have specific functions, such as the mouths of mammals and the roots of trees. The souls of living beings are ordered by Aristotle in a hierarchy. Plants have a vegetative or nutritive soul, which consists of the powers of growth, nutrition, and reproduction. Animals have, in addition, the powers of perception and locomotion—they possess a sensitive soul, and every animal has at least one sense-faculty, touch being the most universal. Whatever can feel at all can feel pleasure; hence, animals, which have senses, also have desires. Humans, in addition, have the power of reason and thought (logismos kai dianoia), which may be called a rational soul. The way in which Aristotle structured the soul and its faculties influenced not only philosophy but also science for nearly two millennia. Aristotle’s theoretical concept of soul differs from that of Plato before him and René Descartes (1596–1650) after him. A soul, for him, is not an interior immaterial agent acting on a body. Soul and body are no more distinct from each other than the impress of a seal is distinct from the wax on which it is impressed. The parts of the soul, moreover, are faculties, which are distinguished from each other by their operations and their objects. The power of growth is distinct from the power of sensation because growing and feeling are two different activities, and the sense of sight differs from the sense of hearing not because eyes are different from ears but because colours are different from sounds. The objects of sense come in two kinds: those that are proper to particular senses, such as colour, sound, taste, and smell, and those that are perceptible by more than one sense, such as motion, number, shape, and size. One can tell, for example, whether something is moving either by watching it or by feeling it, and so motion is a “common sensible.” Although there is no special organ for detecting common sensibles, there is a faculty that Aristotle calls a “central sense.” When one encounters a horse, for example, one may see, hear, feel, and smell it; it is the central sense that unifies these sensations into perceptions of a single object (though the knowledge that this object is a horse is, for Aristotle, a function of intellect rather than sense). Besides the five senses and the central sense, Aristotle recognizes other faculties that later came to be grouped together as the “inner senses,” notably imagination and memory. Even at the purely philosophical level, however, Aristotle’s accounts of the inner senses are unrewarding. britannica.com

Philosophy of mind of Aristotle

Aristotle regarded psychology as a part of natural philosophy, and he wrote much about the philosophy of mind. This material appears in his ethical writings, in a systematic treatise on the nature of the soul (De anima), and in a number of minor monographs on topics such as sense-perception, memory, sleep, and dreams. For Aristotle the biologist, the soul is not—as it was in some of Plato’s writings—an exile from a better world ill-housed in a base body. The soul’s very essence is defined by its relationship to an organic structure. Not only humans but beasts and plants too have souls, intrinsic principles of animal and vegetable life. A soul, Aristotle says, is “the actuality of a body that has life,” where life means the capacity for self-sustenance, growth, and reproduction. If one regards a living substance as a composite of matter and form, then the soul is the form of a natural—or, as Aristotle sometimes says, organic—body. An organic body is a body that has organs—that is to say, parts that have specific functions, such as the mouths of mammals and the roots of trees. The souls of living beings are ordered by Aristotle in a hierarchy. Plants have a vegetative or nutritive soul, which consists of the powers of growth, nutrition, and reproduction. Animals have, in addition, the powers of perception and locomotion—they possess a sensitive soul, and every animal has at least one sense-faculty, touch being the most universal. Whatever can feel at all can feel pleasure; hence, animals, which have senses, also have desires. Humans, in addition, have the power of reason and thought (logismos kai dianoia), which may be called a rational soul. The way in which Aristotle structured the soul and its faculties influenced not only philosophy but also science for nearly two millennia. Aristotle’s theoretical concept of soul differs from that of Plato before him and René Descartes (1596–1650) after him. A soul, for him, is not an interior immaterial agent acting on a body. Soul and body are no more distinct from each other than the impress of a seal is distinct from the wax on which it is impressed. The parts of the soul, moreover, are faculties, which are distinguished from each other by their operations and their objects. The power of growth is distinct from the power of sensation because growing and feeling are two different activities, and the sense of sight differs from the sense of hearing not because eyes are different from ears but because colours are different from sounds. The objects of sense come in two kinds: those that are proper to particular senses, such as colour, sound, taste, and smell, and those that are perceptible by more than one sense, such as motion, number, shape, and size. One can tell, for example, whether something is moving either by watching it or by feeling it, and so motion is a “common sensible.” Although there is no special organ for detecting common sensibles, there is a faculty that Aristotle calls a “central sense.” When one encounters a horse, for example, one may see, hear, feel, and smell it; it is the central sense that unifies these sensations into perceptions of a single object (though the knowledge that this object is a horse is, for Aristotle, a function of intellect rather than sense). Besides the five senses and the central sense, Aristotle recognizes other faculties that later came to be grouped together as the “inner senses,” notably imagination and memory. Even at the purely philosophical level, however, Aristotle’s accounts of the inner senses are unrewarding. britannica.com

Ethics

The surviving works of Aristotle include three treatises on moral philosophy: the Nicomachean Ethics in 10 books, the Eudemian Ethics in 7 books, and the Magna moralia (Latin: “Great Ethics”). The Nicomachean Ethics is generally regarded as the most important of the three; it consists of a series of short treatises, possibly brought together by Ari

|

Aristotle on Activity “According to the Best and Most Final” Virtue

that eudaimonia (happiness) consists in 'activity of soul according to virtue activity to accord with this virtue we shall see that the disputed ... |

|

Nicomachean Ethics

in accordance with the appropriate virtue; then if this is so the human good turns out to be activity of the soul in accordance with virtue |

|

The Highest Good and the Best Activity: Aristotle on the Well-Lived Life

in conformity with excellence or virtue” (NE 1098a16) which Aristotle identifies [E2] Virtuous activity is an activity of the soul in accordance with ... |

|

Divine and Human Happiness in Nicomachean Ethics

soul's activities can accord with more than one virtue the accords with one and only one of those virtues |

|

Aristotle on Well-Being and Intellectual Contemplation

human good (or human well-being) is an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue. He further claims that if there are many virtues |

|

Virtue activity

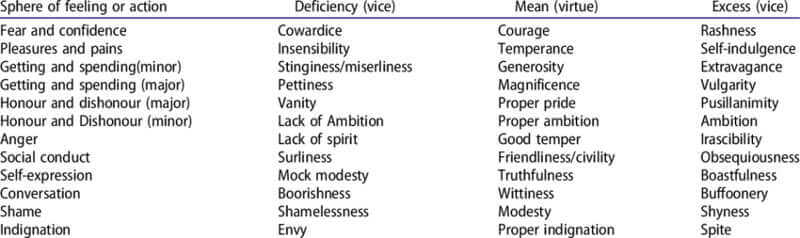

good turns out to be activity of the soul in accordance with virtue. (NE I.7). The Golden Mean. That moral virtue is a mean then |

|

Pride and the Ethics of Aristotle Ann Ward Campion College

virtue. Greatness of Soul. In book 2 of the Nicomachean Ethics Aristotle defines moral virtue as a characteristic or an activity of the soul in accordance |

|

Eudaimonia and Self-Sufficiency in the Nicomachean Ethics

activity of soul in accordance with virtue and if there are several virtues |

|

The Structure of Aristotelian Happiness

in "activity of the soul in accordance with perfect virtue" and perfect virtue seems to include the moral as well as the intellectual virtues. |

|

Aristotles Function Argument - Fas Harvard

The human good therefore is the activity of the rational part of the soul performed well, which is to say, in accordance with virtue (NE 1 7 1098a15–17) Aristotle's |

|

THE NICOMACHEAN ETHICS

So happiness is activity of the soul in accordance with complete virtue 11 Though bad luck may lessen the pleasure of virtuous activity and misfortune may |

|

Some key ideas in the Aristotle reading from Bks I and II of

exercise of virtue requires reason, Aristotle concludes that “human good turns out to be activity of the soul in accordance with virtue” (p 53) -- If Aristotle is right, |