A History of the English Language - Baugh and Cable

A History of the English Language - Baugh and Cable

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge's Linguistics) and Jacek Fisiak's selective and convenient Bibliography of ...

Hystory of Architectural Conservation

Hystory of Architectural Conservation

Bibliography—431 monuments and sites the cross fertilization of these ideas and principles

Religion and the Individual: Belief Practice

Religion and the Individual: Belief Practice

https://www.mdpi.com/books/pdfdownload/book/337

ANNUAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS ABOUT LIFE WRITING 2008

ANNUAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS ABOUT LIFE WRITING 2008

Sacred Memories: The Civil War Monument Movement in Texas. Denton "Zum Zusammenhang von Biographie

Uberty

Uberty

Janet Bodner our copy editors

In This Time without Emperors: The Politics of Ernst Kantorowiczs

In This Time without Emperors: The Politics of Ernst Kantorowiczs

und Stefan George: Beitraige zur Biographie des Historikers bis copy. 'lag bei Himmler auf d tisch': E. Kantorowicz to U. Kiipper 24.

www.ssoar.info Terrorism gender

www.ssoar.info Terrorism gender

https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/39317/ssoar-hsr-2014-3-schraut_et_al-Terrorism_gender_and_history_-.pdf

Migration in Austria

Migration in Austria

Federal Ministry of Science Research and Economy through the Austrian Academic und Geschlecht in den 50er bis 70er Jahren (Frankfurt am Main: Campus

INTERNATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES

INTERNATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES

bibliography and the works it mentions

Contextualizing Sixteenth-Century Lutheran Epitaphs by Lucas

Contextualizing Sixteenth-Century Lutheran Epitaphs by Lucas

Monument for Early Lutheran Ecclesiastical Art.” For burial laws and additional “Cruciger Kaspar

Migration in Austria

innsbruck university pressUNO PRESS

fiUNO PRESS???

Copyright © 2017 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive.New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org.

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimefi

Published in the United States by

University of New Orleans Press

ISBN: 9781608011452

UNO PRESS

Published and distributed in Europe

by Innsbruck University PressISBN: 9783903122802

Publication of this volume has been made possible through a generous grant by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). e Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: e Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. e College of Liberal Arts at the University of New Orleans, as well as the Vice Rectorate for Research and the International Relations Oce of the University ofInnsbruck provided additional nancial support.

Contemporary Austrian Studies

Sponsored by the University of New Orleans

and University of InnsbruckEditors

Associate Editor

Advisory Board

Copy Editor

Production Editors

ex o?cio ex o?cioTable of Contents

I. INTRODUCTION

Photo Essay: Шe Bakkar Family

from Aleppo, Syria - Frontpage RefugeesШe History and Memory of Migration

in Post-War Austria: Current Trends and Future ChallengesII. FROM THE LATE HABSBURG EMPIRE TO WORLD

WAR II

Migration Patterns in the Late Habsburg Empire

III. POST?WORLD WAR II

In Transit or Asylum Seekers?

Austria and the Cold War Refugees from the Communist BlocAustria Attractive for Guest Workers?"

Recruitment of Immigrant Labor in Austria in the 1960s and 1970sШe Other Colleagues" - Labor

Verena Lorber, 161

Eva Tamara Asboth/Silvia Nadjivan, 187IV. THE REFUGEE CRISIS" TODAY AND ITS

REFLECTION IN SOCIETY AND THE ARTS

Andreas . Müller/Andreas Oberprantacher, 217Christiane Hintermann,

243Manfred Kohler,

257Book Reviews

(assisted by Agnes Meisinger), ed.,Sarah Cramsey: Tara Zahra,

279(W.W. Norton & Co.: 2016) James Weingartner: Marco Büchl, 287

Peter Karsten,

(Bennington, Vermont: Merriam Press, 2016) Winfried Garscha: Hellmut Butterweck, 291 (Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2016) Günter Bischof: Florian Traussnig, 297Georg Hofimann,

Robert Mark Spaulding: Maximilian Graf, 305 (Vienna: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften 2016) Dirk Rupnow: Cornelia Wilhelm, ed., 309 (New York: Berghahn 2017)List of Authors

315Preface

Günter Bischof/Dirk Rupnow

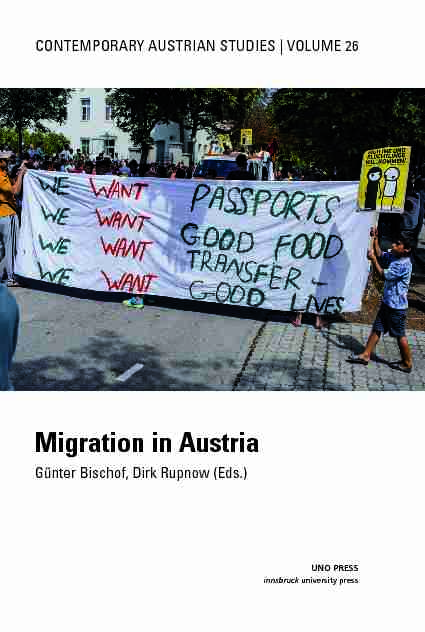

At the height of the so-called "refugee crisis" during the summer of2015, the Austrian Student Organization

organized a demonstration outside the main Austrian government's refugee camp, Traiskirchen, in Lower Austria. e students, supported by the NGO , protested under the heading, "United We Stand for Refugee Rights in Traiskirchen." Traiskirchen Refugee Camp, located 20 kilometers south of Vienna, was formerly used for military barracks and an ocer training center that had been re-opened in the 1950s to accommo- date refugees coming to Austria during Cold War crises in the Communist Bloc (Hungary in 1956/57, Czechoslovakia in 1968/69, Poland in 1981/82, GDR and Romania in 1989/90). In the summer of 2015, Traiskirchen was overcrowded with refugees who had made it through the Balkans and even- tually arrived in Austria. e iconic refugee camp was in the Austrian news all summer. e demands of the protesters gathering outside that camp on July 26, 2015 are clearly outlined in the banners they carried in the picture on the cover of this volume. Refugees were asking for their basic human needs being met: passports and the right to transfer through Austria to places beyond (Germany, Sweden), and decent food and living condi- tions. One poster also said, "Muslims and Refugees are Welcome Here!," referencing what became known that summer as the "culture of welcome" "). is, interestingly, was the Austrian "word of the year" in 2015; the "ugly phrase of the year," on the opposite side, was "I am not a racist, but ...". In Germany, it was " " ("refugees"), while the "sentence of the year" was Angela Merkel's phrase " " ("We have managed again and againwe can do it!"). Austria, of course, did not become a "migration society" overnight in 2015. Austrians have long ignored the fact that the country has been changing enormously after World War II as a result of a continuous inux of migrants. e turning point in postwar Austrian history came in the1960s, with the beginning of organized recruitment of foreign laborers

from Turkey and Yugoslavia. But a longer history needs to be kept in mind to understand and contextualize these postwar Austrian developments. ere is the complex history of the multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire and its internal migration: millions of people moved from Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and Galicia to the expanding capital city of Vienna. is internal migration segued into overseas emigration, mostly to the United States. In the four decades before World War I, as many as four to ve million people left the Habsburg Empire. As in today's Vienna, as early as 1840, the population was composed of 40% "foreigners." e discussion after the end of World War I and the collapse of the Habsburg Empire revolved around who to admit as citizens to the newly formed Republic of Austria and who to exclude. An Austrian history of migration also needs to consider the grim chapter of forced labor (" ") during the Nazi period. e Nazis put to work 15 million slave laborers in Germany and all over occupied Europe during World War II; around three million of them perished. In the fall of 1944, around one million slave laborers worked on the territory that is Austria today. e history of millions of Displaced Persons (DPs), refugees, and German ethnic expellees ("") has been also part and parcel of Austrian migration history after the end of World War II. And there are also hundreds of thousands of Cold War refugees from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland that mostly used Austria as a transfer point (only a few thousand stayed) who need to be considered. In 2015 Austria had an all-time high in-migration of ca. 110,000 peo- plemore than in the early 1990s when Austria accepted tens of thou- sands of refugees from "the Yugoslav Wars." 88,340 applications for asylum ("international protection") were led in 2015. Austria was the third largest recipient of asylum seekers in the European Union and allowed more than800,000 refugees to transit the country. It was civil society and its "welcom-

ing culture" that managed the so-called "refugee crisis," much more so than an apathetic political class. Pressured by a xenophobic and nativist popular press, Austrian politicians reacted by pondering a cap for asylum applica tions, including the proclamation of a state of emergency for the whole country. Some Austrian politicians, following the example of Australia, where refugees are put into camps on ofishore islands, have been suggesting "concentration camps" on Greek islands, North Africa, or the Caucasus for people on the move to Europe. Similar to other countries in the European Union (and the United States), the ongoing "refugee crisis" has produced a populist political back- lash. Ever since the 1990s, the nativist Austrian "Freedom Party" (FPÖ) has been dictating the domestic agenda on limiting the number of immigrants/ asylum seekers with its xenophobic, anti-immigrant discourse. During the recent Austrian Presidential election, FPÖ candidate Norbert Hofer ran a strong second with 47 percent of the vote. In the past few years, the FPÖ has consistently been the strongest party in public opinion polls all over Austria. A national federal election is scheduled for the fall of 2017. e governing Socialist-Conservative SPÖ-ÖVP "grand coalition" has tried to coopt the anti-immigrant public mood to stay competitive in this shrill nativist national public discourse. It remains to be seen how these migration and societal diversity issues will be addressed in the next national election. It would be a surprise if they did not dominate the political landscape, given the staunch anti-Muslim racism that has been profiered and introduced into the public discourse by the populist right-wing FPÖ. Austria is not alone in the Western world in facing such a growing anti-immigrant consensus. is comes at a time when, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency, an astounding 65.3 million refugees are on the move worldwide, leaving their troubled home countries behind.1.3 million applied for asylum in the European Union in 2015. In the

United States, some eleven million undocumented immigrants dened the2016 presidential election campaign. e new populist administration of

President Donald Trump is trying to remove these undocumented immi- grants from the U.S. and is stirring up fears about "radical Islamic terror- ism," suggesting to the American people a strong linkage between what some people call "illegal migrants," terrorism, and national security, while also profiering openly anti-Muslim sentiments. Given this populist, xenophobic, and highly emotionalized anti-immi- gration political environment in the West, it is hard to make the rational voices of scholars heard when it comes to migration and diversity issues. Scholars do not pretend to have easy answers and quick xes at hand. ey insist on measured and difierentiated approaches to migration, including the complex and deep historical contexts of the continuous movement of people due to political (conicts and wars), economic (globalization), and increasingly environmental changes. Dealing with and accepting immi- gration as a continuous historical force means embracing diversity in our societies. Making migrants visible in our historical master narratives is a prerequisite for recognizing social diversity in society and giving newcom- ers opportunities to participate. Migration research and scholarship must therefore guard itself against accepting the prevailing public discourses that are deeply mired in highly problematic presumptions about "integration" of migrants and imagined images of refugees always "drowning" in metaphors of water, natural disasters, and threats ("ood," "tsunami," etc.). is interdisciplinary volume ofiers methodologically innovative approaches to Austria's coping with issues of migration past and present. ese essays show Austria's long history as a migration country. Austrians themselves had been on the move for the past 150 years to nd new homes and build better lives. After World War II, the economy improved and prosperity set in, so Austrians tended to stay at home. Austria's growing prosperity made the country attractive to potential immigrants. After the war, tens of thousands of "ethnic Germans" expelled from Eastern Europe settled in Austria. Starting in the 1950s "victims of the Cold War" (Hungarians, Czechs, and Slovaks) began looking for political asylum in Austria. Since the 1960s, Austria has been recruiting a growing number of "guest workers" from Turkey and Yugoslavia to make up for the labor missing in the industrial and service economies. Recently, refugees from the arc of crisis from Afghanistan to Syria to Somalia have braved perilous journeys to build new lives in a more peaceful and prosperous Europe.With Heinz Tesarek's photo essay, enters

uncharted territory. We have always tried to illustrate our volumes, but we have never before invited a photo artist to contribute a photographic essay to illuminate the emotional depth of the ongoing migration issues capti- vating Europeans and Austrians. Tesarek has followed the Bakkar family of Aleppo, Syria, over three days from Hungary, via Austria to Germany, on September 5 to 7 in the summer of 2015. Like thousands of Austrian fami- lies seeking refuge from political turmoil and a better life during the World War II era all over the world, Syrian, Iraqi, Afghani, Somali, Sudanese, and Nigerian families have been seeking to escape the (civil) war-torn regions of their homelands and build better lives in Europe (and America). Historian and co-editor Dirk Rupnow's introductory essay shows how the history of migration during the Second Austrian Republic has been orphaned by historians and is non-present in the grand narratives of twentieth-century Austrian history. Discussing recent trends and delving more deeply in the history of the1960s and 1970s labor migrations, he also analyzes some of the current challenges for historical research, grappling with the issues of migration and diversity in contemporary Austrian history. He also presents projects that deal with the documentation and archiving of migration. Annemarie Steidl's essay provides a deeper historical contextualization of migratory patterns in the late Habsburg Monarchy, wherein people fromquotesdbs_dbs28.pdfusesText_34[PDF] Bibliographie Musculation - Support Technique

[PDF] bibliographie Naples

[PDF] Bibliographie NT - Anciens Et Réunions

[PDF] Bibliographie option lettres modernes (ULM) 2016-2017 - Anciens Et Réunions

[PDF] Bibliographie Ouvrages disponibles au centre de - Saint

[PDF] BIBLIOGRAPHIE Ouvrages Theodor W. ADORNO, La Dialectique

[PDF] Bibliographie pluralité nominale et verbale Abeillé A., 2006

[PDF] Bibliographie Pôle Nord / Pôle Sud

[PDF] bibliographie pour la question d`histoire ancienne - Agriculture Et Foresterie

[PDF] Bibliographie pour la seconde - Anciens Et Réunions

[PDF] Bibliographie pour le cours d`Histoire - Histoire

[PDF] Bibliographie pour l`Agrégation - Nicolas Patrois - Des Bandes Dessinées

[PDF] BIBLIOGRAPHIE POUR PREPARER LE CONCOURS Absolument

[PDF] bibliographie primaire : suggestions de lectures - France