You may take one two or three math courses in General Social

You may take one two or three math courses in General Social

WANT TO TAKE HIGH SCHOOL TS/SN MATH COURSES ONCE YOU ARE ENROLLED AT DAWSON? In their final years of high school a number of students either choose not to

Math 412. The Symmetric Group Sn.

Math 412. The Symmetric Group Sn.

DEFINITION: The symmetric group Sn is the group of bijections from any set of n objects which we usu- ally call simply {1

Series

Series

Definition 4.1. Let (an) be a sequence of real numbers. The series. ?. ? n=1 an converges to a sum S ? R if the sequence (Sn) of partial sums. Sn =.

TABLEAU DES PRÉALABLES

TABLEAU DES PRÉALABLES

TS ou SN 4 e secondaire. TS ou SN 5 e secondaire Sciences humaines (profil avec math). Sciences humaines et langues cultures et mondes (sans math).

Representation Theory

Representation Theory

one should recall that in first approximation

Math CST 5 ou Math TS ou SN 4 Préalables particuliers Math TS ou

Math CST 5 ou Math TS ou SN 4 Préalables particuliers Math TS ou

Pilotage d'aéronefs. ?. Tech. de laboratoire. ?. (profil biotechnologies ou profil chimie analytique). ?. Tech. de génie chimique.

Recovering Functions Defined on $Bbb S^{n-1} $ by Integration on

Recovering Functions Defined on $Bbb S^{n-1} $ by Integration on

Apr 2 2017 arXiv:1704.00349v1 [math.AP] 2 Apr 2017 ... For a point ? in Sn?1 define the following n ? 2 dimensional subsphere of Sn?1: Sn?2.

6. Conjugation in S One thing that is very easy to understand in

6. Conjugation in S One thing that is very easy to understand in

One thing that is very easy to understand in terms of Sn is conjuga- tion. Definition 6.1. Let g and h be two elements of a group G. The element ghg-1 is called

CONJUGATION IN A GROUP 1. Introduction A reflection across one

CONJUGATION IN A GROUP 1. Introduction A reflection across one

In these examples different conjugacy classes in a group are disjoint: they don't overlap To carry ?1 to ?2 by conjugation in Sn

REPRESENTATIONS OF THE SYMMETRIC GROUP Contents 1

REPRESENTATIONS OF THE SYMMETRIC GROUP Contents 1

Sept 1 2010 In this case

[PDF] Series SN Notation

[PDF] Series SN Notation

SN is generally used to denote the sum to N terms of a series In the series 1 + 3 + 5+7+9+ S4 = 16 That is the sum of the

Maths TS CST SN: faire le bon choix - ChallengeU

Maths TS CST SN: faire le bon choix - ChallengeU

9 mar 2021 · Les maths Sciences Naturelles (SN) et Technico-Sciences (TS) sont ce qu'on appelle communément « les maths fortes » Attention! Bien qu'ils

[PDF] Séries numériques

[PDF] Séries numériques

29 avr 2014 · Maths en Ligne Séries numériques UJF Grenoble Définition 2 On dit que la série ? un converge vers s si la suite des sommes partielles

[PDF] Cours danalyse 1 Licence 1er semestre

[PDF] Cours danalyse 1 Licence 1er semestre

Définition 2 1 1 Une relation (ou proposition) est une phrase affirmative qui est vraie ou fausse (V ou F en abrégé) Une relation porte sur des objets

[PDF] MATHÉMATIQUES DISCRÈTES

[PDF] MATHÉMATIQUES DISCRÈTES

Définition I 1 (Sous-ensembles) L'ensemble A est un sous-ensemble de B si tous les éléments de A sont des éléments de

Quel cours de mathématiques choisir en 4e et en 5e secondaire?

Quel cours de mathématiques choisir en 4e et en 5e secondaire?

Par exemple si votre enfant choisit la séquence Sciences naturelles (SN) il poursuivra probablement dans cette voie en 4e et en 5e secondaire

Aide-mémoire – Mathématiques – Secondaire 5 – SN - Alloprof

Aide-mémoire – Mathématiques – Secondaire 5 – SN - Alloprof

offre un résumé du contenu étudié en mathématiques de la 5e secondaire séquence Sciences Naturelles (SN) Par définition ?x?=max{?xx}

[PDF] Structures Algébriques 1 : Résumé de cours

[PDF] Structures Algébriques 1 : Résumé de cours

deF on peut effectuer la division euclidienne de a par g : La composition des applications munit Sn d'une structure de groupe : la composée de

[PDF] [PDF] Séries - Exo7 - Cours de mathématiques

[PDF] [PDF] Séries - Exo7 - Cours de mathématiques

Définitions – Série géométrique 1 1 Définitions Définition 1 Soit (uk)k?0 une suite de nombres réels (ou de nombres complexes) On pose Sn = u0 + u1 +

[PDF] MATHS 110c cHAPITRE III : NOTIONS DE LIMITES

[PDF] MATHS 110c cHAPITRE III : NOTIONS DE LIMITES

n'utiliserons la définition de la limite "avec des ?" que dans des exercices théoriques Dans les calculs pratiques de limite (voir la fin du paragraphe) nous

C'est quoi les math SN ?

Les maths Sciences Naturelles (SN) et Technico-Sciences (TS) sont ce qu'on appelle communément « les maths fortes ». Attention Bien qu'ils soient un peu différents, les deux cours répondent aux mêmes exigences et offrent les mêmes débouchés pour le Cégep et l'université.9 mar. 2021Pourquoi faire math SN ?

2- La séquence Sciences naturelles (SN)

Cette séquence s'adresse tout particulièrement au jeune qui désire se diriger vers les sciences pures (ou naturelles) et la recherche. Si ce choix interpelle particulièrement votre enfant, il est important de vous assurer qu'il correspond bien à sa personnalité.C'est quoi les mathématiques 436 ?

On présente les mathématiques autrefois bien connues sous le nom de ?6» comme des mathématiques ?ortes». Voilà un problème de cadrage. Présenter les mathématiques comme «régulières» ou ?ortes» dans le langage pédagogique, c'est déjà porter ex ante une limite au jugement d'un adolescent incertain ou démotivé.- Mathématique 526 : transitoire : enseignement secondaire [Ministère de l'éducation], Direction de la formation générale des jeunes ; [coordination et conception, Mihran Djiknavorian ; conception et rédaction, Maurice Couillard, Denis de Champlain]

CONJUGATION IN A GROUP

KEITH CONRAD

1.Introduction

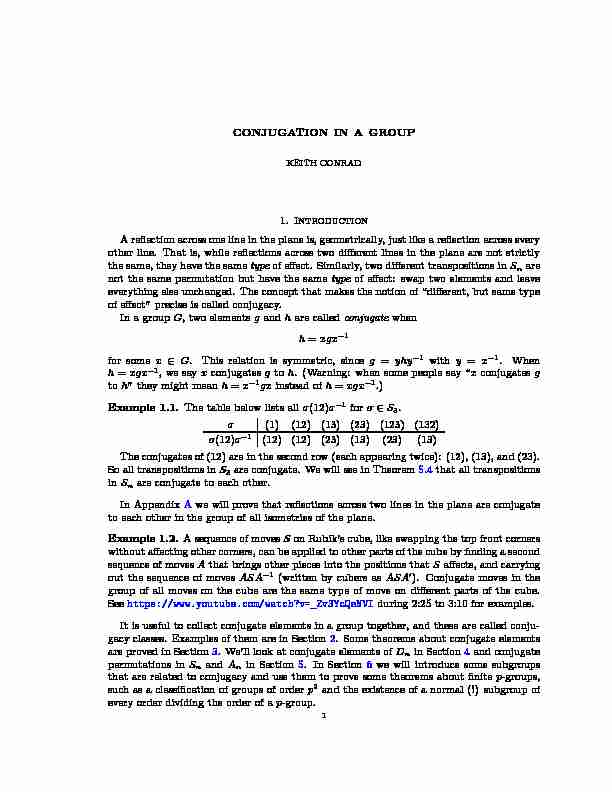

A re ection across one line in the plane is, geometrically, just like a re ection across every other line. That is, while re ections across two dierent lines in the plane are not strictly the same, they have the sametypeof eect. Similarly, two dierent transpositions inSnare not the same permutation but have the sametypeof eect: swap two elements and leave everything else unchanged. The concept that makes the notion of \dierent, but same type of eect" precise is called conjugacy. In a groupG, two elementsgandhare calledconjugatewhen h=xgx1 for somex2G. This relation is symmetric, sinceg=yhy1withy=x1. When h=xgx1, we sayxconjugatesgtoh. (Warning: when some people say \xconjugatesg toh" they might meanh=x1gxinstead ofh=xgx1.)Example 1.1.The table below lists all(12)1for2S3.

(1) (12) (13) (23) (123) (132) (12)1(12) (12) (23) (13) (23) (13) The conjugates of (12) are in the second row (each appearing twice): (12), (13), and (23). So all transpositions inS3are conjugate. We will see in Theorem5.4 that all transp ositions inSnare conjugate to each other.In Appendix

A w ewill pro vethat re ections across t wolines in the plane are c onjugate to each other in the group of all isometries of the plane. Example 1.2.A sequence of movesSon Rubik's cube, like swapping the top front corners without aecting other corners, can be applied to other parts of the cube by nding a second sequence of movesAthat brings other pieces into the positions thatSaects, and carrying out the sequence of movesASA1(written by cubers asASA0). Conjugate moves in the group of all moves on the cube are the same type of move on dierent parts of the cube. Seehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zv3YcQeNVIduring 2:25 to 3:10 for examples. It is useful to collect conjugate elements in a group together, and these are called conju- gacy classes. Examples of them are in Section 2 . Some theorems about conjugate elements are proved in Section 3 . We'll look at conjugate elements ofDnin Section4 and conjugate permutations inSnandAnin Section5 . In Section6 w ewill in troducesome subgroups that are related to conjugacy and use them to prove some theorems about nitep-groups, such as a classication of groups of orderp2and the existence of a normal (!) subgroup of every order dividing the order of ap-group. 12 KEITH CONRAD

2.Conjugacy classes: definition and examples

For an elementgof a groupG, itsconjugacy classis the set of elements conjugate to it: fxgx1:x2Gg: Example 2.1.IfGis abelian thenxgx1=gfor allx;g2G: everygis its own conjugacy class. This characterizes abelian groups: to say eachg2Gis its own conjugacy class means xgx1=gfor allxandginG, which saysxg=gxfor allxandg, soGis abelian.

Example 2.2.The conjugacy class of (12) inS3isf(12);(13);(23)g, as we saw in Example 1.1 . Similarly, the reader can check the conjugacy class of (123) isf(123);(132)g. The conjugacy class of (1) is justf(1)g. SoS3has three conjugacy classes: f(1)g;f(12);(13);(23)g;f(123);(132)g: Example 2.3.InD4=hr;si, there are ve conjugacy classes: f1g;fr2g;fs;r2sg;fr;r3g;frs;r3sg: The members of a conjugacy class ofD4are dierent but have the same type of eect on a square:randr3are a 90 degree rotation in some direction,sandr2sare a re ection across a diagonal, andrsandr3sare a re ection across an edge bisector.Example 2.4.There are ve conjugacy classes inQ8:

f1g;f1g;fi;ig;fj;jg;fk;kg: Example 2.5.There are four conjugacy classes inA4: f(1)g;f(12)(34);(13)(24);(14)(23)g; Notice the 3-cycles (123) and (132) arenotconjugate inA4. All 3-cycles inA4are conjugate in the larger groupS4,e.g., (132) = (23)(123)(23)1and the conjugating permutation (23) is not inA4. In these examples, dierent conjugacy classes in a group aredisjoint: they don't overlap at all. This will be proved in general in Section 3 . Also, the sizes of dierent conjugacy classes are not all the same, but these sizes all divide the size of the group. We will see inSection

6 wh ythis is true. The idea of conjugation can be applied not just to elements, but to subgroups. IfHG is a subgroup andg2G, the set gHg1=fghg1:h2Hg

is a subgroup ofG, called naturally enough aconjugate subgrouptoH. It's a subgroup since it contains the identity (e=geg1) and is closed under multiplication and inversion: (ghg1)(gh0g1) =g(hh0)g1and (ghg1)1=gh1g1. Unlike dierent conjugacy classes, dierent conjugate subgroups are not disjoint: they all contain the identity. Example 2.6.WhileD4has 5 conjugacy classes of elements (Example2.3 ), it has 8 conjugacy classes of subgroups. In total there are 10 subgroups ofD4: hri=f1;r;r2;r3g;hr2i=f1;r2g;hr2;si=f1;r2;s;r2sg;hr2;rsi=f1;r2;rs;r3sg; D4: In this list the subgroupshsiandhr2siare conjugate, as arehrsiandhr3si: checkrhsir1= hr2siandrhrsir1=hr3si. The other six subgroups ofD4are conjugate only to themselves.CONJUGATION IN A GROUP 3

We will not discuss conjugate subgroups much, but the concept is important. For in- stance, a subgroup is conjugate only to itself precisely when it is a normal subgroup.3.Some basic properties of conjugacy classes

Lemma 3.1.In a group,(xgx1)n=xgnx1for all positive integersn. Proof.This is left to the reader as an exercise using induction. The equation is in fact true for alln2Z. Theorem 3.2.All the elements of a conjugacy class have the same order. Proof.This is sayinggandxgx1have the same order. By Lemma3.1 , (xgx1)n=xgnx1 for alln2Z+, so ifgn= 1 then (xgx1)n=xgnx1=xx1=e, and if (xgx1)n= 1 then xg nx1=e, sogn=x1x=e. Thus (xgx1)n= 1 if and only ifgn= 1, sogandxgx1 have the same order.The converse to Theorem

3.2 is false: elemen tsof the same order in a group need not b e conjugate in that group. This is clear in abelian groups, where dierent elements are never conjugate but could have the same order. Looking at the nonabelian examples in Section 2 , inD4there are ve elements of order two spread across 3 conjugacy classes. Similarly, there are non-conjugate elements of equal order inQ8andA4. But inS3, elements of equal order inS3are conjugate. Amazingly, this is the largest example of a nite group where that property holds: up to isomorphism, the only nontrivial nite groups where all elements of equal order are conjugate areZ=(2) andS3. A proof is given in [3] and [7], and depends on the classication of nite simple groups. A conjugacy problem aboutS3that remains open, as far as I know, is the conjecture thatS3is the only nontrivial nite group (up to isomorphism) in which dierent conjugacy classes all have dierent sizes. Corollary 3.3.IfHis a cyclic subgroup ofGthen every subgroup conjugate toHis cyclic.Proof.WritingH=hyi=hyn:n2Zg,

gHg1=fgyng1:n2Zg=f(gyg1)n:n2Zg=hgyg1i;

sogHg1is cyclic with a generator being a conjugate (byg) of a generator ofH.Let's verify the observation in Section

2 that dieren tconjugacy classes are disjoin t. Theorem 3.4.LetGbe a group andg;h2G. If the conjugacy classes ofgandhoverlap, then the conjugacy classes are equal. Proof.We need to show every element conjugate togis also conjugate toh, andvice versa. Since the conjugacy classes overlap, we havexgx1=yhy1for somexandyin the group.Therefore

g=x1yhy1x= (x1y)h(x1y)1; sogis conjugate toh. Each element conjugate togiszgz1for somez2G, and zgz1=z(x1y)h(x1y)1z1= (zx1y)h(zx1y)1;

which shows each element ofGthat is conjugate togis also conjugate toh. To go the other way, fromxgx1=yhy1writeh= (y1x)g(y1x)1and carry out a similar calculation.4 KEITH CONRAD

Theorem

3.4 sa yseac helemen tof a group b elongsto j ustone conjugacy class. W ecall an element of a conjugacy class arepresentativeof that class. A conjugacy class consists of allxgx1for xedgand varyingx. Instead we can look at allxgx1for xedxand varyingg. That is, instead of looking at all the elements conjugate togwe look at all the waysxcan conjugate the elements of the group. This \conjugate-by-x" function is denoted x:G!G, so x(g) =xgx1.Theorem 3.5.Each conjugation function

x:G!Gis an automorphism ofG.Proof.For allgandhinG,

x(g) x(h) =xgx1xhx1=xghx1= x(gh); so xis a homomorphism. Sinceh=xgx1if and only ifg=x1hx, the function xhas inverse x1, so xis an automorphism ofG.Theorem

3.5 explains wh yc onjugateelemen tsin a group Gare \the same except for the point of view": they are linked by an automorphism ofG, namely some map x. This means an element ofGand its conjugates inGhave the same group-theoretic properties, such as: having the same order, being anm-th power, being in the center, and being a commutator. Likewise, a subgroupHand its conjugatesgHg1have the same group-theoretic properties.Automorphisms ofGhaving the form

xare calledinner automorphisms. They are the only automorphisms that can be written down without knowing extra information aboutG (such as being toldGis abelian or thatGis a particular matrix group). For someGevery automorphism ofGis an inner automorphism. This is true for the groupsSnwhenn6= 6 (that's right:S6is the only symmetric group with an automorphism that isn't conjugation by a permutation). The groups GL n(R) whenn2 have extra automorphisms: since (AB)>=B>A>and (AB)1=B1A1, the functionf(A) = (A>)1on GLn(R) is an automorphism and it is not inner. Here is a simple result where inner automorphisms tell us something about all automor- phisms of a group. Theorem 3.6.IfGis a group with trivial center, then the groupAut(G)also has trivial center. Proof.Let'2Aut(G) and assume'commutes with all other automorphisms. We will see what it means for'to commute with an inner automorphism x. Forg2G, x)(g) ='( x(g)) ='(xgx1) ='(x)'(g)'(x)1 and x')(g) = x('(g)) =x'(g)x1; so having'and xcommute means, for allg2G, that '(x)'(g)'(x)1=x'(g)x1()x1'(x)'(g) ='(g)x1'(x); sox1'(x) commutes with every value of'. Since'is onto,x1'(x)2Z(G). The center ofGis trivial, so'(x) =x. This holds for allx2G, so'is the identity automorphism.We have proved the center of Aut(G) is trivial.

CONJUGATION IN A GROUP 5

4.Conjugacy classes inDn

In the groupDnwe will show rotations are conjugate only to their inverses and re ections are either all conjugate or fall into two conjugacy classes. Theorem 4.1.The conjugacy classes inDnare as follows. (1)Ifnis odd, the identity element:f1g, (n1)=2conjugacy classes of size2:fr1g;fr2g;:::;fr(n1)=2g, all the re ections:fris: 0in1g. (2)Ifnis even, two conjugacy classes of size1:f1g,frn2 g, n=21conjugacy classes of size2:fr1g;fr2g;:::;fr(n2 1)g, the re ections fall into two conjugacy classes:fr2is: 0in2 1gand fr2i+1s: 0in2 1g. Proof.Every element ofDnisriorrisfor some integeri. Therefore to nd the conjugacy class of an elementgwe will computerigriand (ris)g(ris)1.The formulas

r irjri=rj;(ris)rj(ris)1=rj asivaries show the only conjugates ofrjinDnarerjandrj. Explicitly, the basic formula sr js1=rjshows usrjandrjare conjugate; we need the more general calculation to be sure there is nothing further thatrjis conjugate to.To nd the conjugacy class ofs, we compute

r isri=r2is;(ris)s(ris)1=r2is:Asivaries,r2isruns through the re

ections in whichroccurs with an exponent divisible by 2. Ifnis odd then every integer modulonis a multiple of 2 (since 2 is invertible modn we can solvek2imodnforino matter whatkis). Therefore whennis odd fr2is:i2Zg=frks:k2Zg; so every re ection inDnis conjugate tos. Whennis even, however, we only get half the re ections as conjugates ofs. The other half are conjugate tors: r i(rs)ri=r2i+1s;(ris)(rs)(ris)1=r2i1s:Asivaries, this gives usfrs;r3s;:::;rn1sg.

That re

ections inDnform either one or two conjugacy classes, depending on the parity ofn, corresponds to a geometric feature of re ections: for oddnall re ections inDnlook the same (Figure 1 ) { re ecting across a line connecting a vertex and the midpoint on the opposite side { but for evennthe re ections inDnfall into two types {therevensre ect across a line through pairs of opposite vertices and theroddsre ect across a line through midpoints of opposite sides (Figure 25.Conjugacy classes inSnandAn

The following tables list a representative from each conjugacy class inSnandAnfor3n6, along with the size of the conjugacy classes. Conjugacy classes disjointly cover

a group, by Theorem 3.4 , so the conjugacy class sizes add up ton! forSnandn!=2 forAn.6 KEITH CONRAD

Figure 1.Lines of Re

ection forn= 3 andn= 5.Figure 2.Lines of Re ection forn= 4 andn= 6.S 3A3Rep.(1)(123)(12)(1)(123)(132)

Size123111

S 4ASize136681344

SSize1101520202430

A5Rep.(1)(12345)(21345)(12)(34)(123)

Size112121520

SSize11515404045

Size9090120120144

ASize1404045727290

CONJUGATION IN A GROUP 7

Notice elements ofAncan be conjugate inSnwhilenotbeing conjugate inAn, such as (123) and (132) forn= 3 andn= 4. (See Example2.5 .) The permutations inS3andS4 that conjugate (123) to (132) are not even, so (123) and (132) are not conjugate inA3or A4. They are conjugate inA5: (132) =(123)1for= (23)(45).

As a rst step in describing conjugacy classes inSn, let's nd the conjugates of ak-cycle. Theorem 5.1.For each cycle(i1i2:::ik)inSnand each2Sn, (i1i2:::ik)1= ((i1)(i2):::(ik)): Before proving this formula, let's see in two examples how it works.Example 5.2.InS5, let= (13)(254). Then

(1432)1= (13)(254)(1432)(245)(13) = (1532) while ((1)(4)(3)(2)) = (3215) since(1) = 3,(4) = 2,(3) = 1, and(2) = 5.Clearly (1532) = (3215).

Example 5.3.InS7, let= (13)(265). Then

(73521)1= (13)(265)(73521)(256)(13) = (12637) and ((7)(3)(5)(2)(1)) = (71263) = (12637).Now we prove Theorem

5.1 Proof.Let=(i1i2:::ik)1. We want to showis the cyclic permutation of the numbers(i1);(i2);:::;(ik). That means two things: Showsends(i1) to(i2),(i2) to(i3);:::, and nally(ik) to(i1). Showdoes not move a number other than(i1);:::;(ik). The second step is essential. Just knowing a permutation cyclically permutes certain num- bers does not mean itisthe cycle built from those numbers, since it could move other numbers we haven't looked at yet. (For instance, if(1) = 2 and(2) = 1,need not be (12). The permutation (12)(345) also has that behavior.)What doesdo to(i1)? The eect is

((i1)) = ((i1i2:::ik)1)((i1)) = (((i1i2:::ik)1)(i1) =(i1i2:::ik)(i1) =(i2): (The \(i1)" at the ends is not a 1-cycle, but denotes the point where a permutation is being evaluated.) Similarly,((i2)) =(i1i2:::ik)(i2) =(i3), and so on up to((ik)) = (i1i2:::ik)(ik) =(i1). Now pick a numberathat is not among(i1);:::;(ik). We want to show(a) =a. That means we want to show(i1i2:::ik)1(a) =a. Sincea6=(ij) forj= 1;:::;k, also1(a) is notijforj= 1;:::;k. Therefore the cycle (i1i2:::ik)does not move1(a), so

its eect on1(a) is to keep it as1(a). Hence (a) = ((i1i2:::ik)1)(a) =(i1i2:::ik)(1(a)) =(1(a)) =a: We now know that every conjugate of a cycle is also a cycle of the same length. Is the converse true,i.e., if two cycles have the same length are they conjugate? Theorem 5.4.All cycles of the same length inSnare conjugate.8 KEITH CONRAD

Proof.Pick twok-cycles, say

(a1a2::: ak);(b1b2::: bk): Choose2Snso that(a1) =b1;:::;(ak) =bk, and letbe an arbitrary bijection from the complement offa1;:::;akgto the complement offb1;:::;bkg. Then, using Theorem 5.1 , we see conjugation bycarries the rstk-cycle to the second. For instance, the transpositions (2-cycles) inSnform a single conjugacy class, as we saw forS3in the introduction. Now we consider the conjugacy class of an arbitrary permutation inSn, not necessarily a cycle. It will be convenient to introduce some terminology. Writing a permutation as a product of disjoint cycles, arrange the lengths of those cycles in increasing order, including1-cycles if there are xed points. These lengths are called thecycle typeof the permutation.1

For instance, inS7the permutation (12)(34)(567) is said to have cycle type (2;2;3). When discussing the cycle type of a permutation, we include xed points as 1-cycles. For instance, (12)(35) inS5is (4)(12)(35) and has cycle type (1;2;2). If we view (12)(35) inS6then it is (4)(6)(12)(35) and has cycle type (1;1;2;2). The cycle type of a permutation inSnis just a set of positive integers that add up ton, which is called apartitionofn. There are 7 partitions of 5:5;1 + 4;2 + 3;1 + 1 + 3;1 + 2 + 2;1 + 1 + 1 + 2;1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1:

Thus, the permutations ofS5have 7 cycle types. Knowing the cycle type of a permutation tells us its disjoint cycle structure except for how the particular numbers fall into the cycles. For instance, a permutation inS5with cycle type (1;2;2) could be (1)(23)(45), (2)(35)(14), and so on. This cycle type of a permutation is exactly the level of detail that conjugacy measures inSn: two permutations inSnare conjugate precisely when they have the same cycle type. Let's understand how this works in an example rst. Example 5.5.We consider two permutations inS5of cycle type (2;3):1= (24)(153); 2= (13)(425):

To conjugate1to2, letbe the permutation inS5that sends the terms appearing in1 to the terms appearing in2in exactly the same order:=2415313425= (14352). Then

11=(24)(153)1=(24)1(153)1= ((2)(4))((1)(5)(3)) = (13)(425);

so11=2.If we had written1and2dierently, say as

1= (42)(531); 2= (13)(542);

then2=11where=4253113542= (1234).

Lemma 5.6.If1and2are disjoint permutations inSn, then11and21are disjoint permutations for all2Sn. Proof.Being disjoint means no number is moved by both1and2. That is, there is noi such that1(i)6=iand2(i)6=i. If11and21are not disjoint, then they both move some number, sayj. Then (check!)1(j) is moved by both1and2, which is a contradiction.1 A more descriptive label might be \disjoint cycle structure", but the standard term is \cycle type".CONJUGATION IN A GROUP 9

Theorem 5.7.Two permutations inSnare conjugate if and only if they have the same cycle type. Proof.Pick2Sn. Writeas a product of disjoint cycles. By Theorem3.5 and Lemma 5.6 ,1will be a product of the-conjugates of the disjoint cycles for, and these -conjugates aredisjointcycles with the same respective lengths. Therefore1has the same cycle type as. For the converse direction, we need to explain why permutations1and2with the same cycle type are conjugate. Suppose the cycle type is (m1;m2;:::). Then1= (a1a2:::am1|{z}

m1terms)(am1+1am1+2:::am1+m2|{z}

m2terms)

and2= (b1b2:::bm1|{z}

m1terms)(bm1+1bm1+2:::bm1+m2|{z}

m2terms);

where the cycles here are disjoint. To carry1to2by conjugation inSn, dene the permutation2Snby:(ai) =bifor alli. Then11=2by Theorems3.5 and 5.4 . (This is exactly the method used to ndin Example5.5 .) Remark 5.8.Theorem5.7 has real-w orldsignicance: it w asa prop ertyof p ermutations that helped the Polish cryptographer Marian Rejewski and his colleagues break an early version of the German military's Enigma code in the years before World War II [ 5 Since the conjugacy class of a permutation inSnis determined by its cycle type, which is a certain partition ofn, the number of conjugacy classes inSnis the number of partitions ofn. The number of partitions ofnis denotedp(n). Here is a table of some values. Check the numbers at the start of the table forn6 agree with the number of conjugacy classes in the tables at the start of this section. n1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 p(n)1 2 3 5 7 11 15 22 30 42 56 77 101 135 The functionp(n) grows quickly,e.g.,p(100) = 190;569;292.Using Theorem

5.7 , there is a type of converse to Theorem 3.2 : although elements of equal order in a group need not be conjugate in the group, conjugacy will occur by working in a larger group.quotesdbs_dbs30.pdfusesText_36[PDF] cours l'air qui nous entoure

[PDF] controle chimie 4ème l'air qui nous entoure

[PDF] quel est le pourcentage du rayonnement solaire qui traverse effectivement l'atmosphère terrestre

[PDF] l'air qui nous entoure 4ème

[PDF] comment appelle t on la couche dans laquelle nous vivons

[PDF] qu'est ce que l'atmosphère terrestre

[PDF] qu'est ce qui mesure la quantité de vapeur d'eau

[PDF] synthese d'un anesthesique la benzocaine correction

[PDF] synthèse du 4-nitrobenzoate d'éthyle

[PDF] synthèse de la benzocaine exercice seconde

[PDF] synthèse de la benzocaine sujet

[PDF] synthèse de la benzocaine terminale s

[PDF] cours de chimie therapeutique 3eme année pharmacie

[PDF] qcm chimie thérapeutique